Ancient Cemeteries of Astana: From Sacred Places to Forgotten Stories

The cemeteries of Kazakhstan’s capital continue to preserve the memory of its past.

Читайте этот материал на русском .

The Muslim cemetery Karaotkel, located on Astana’s so-called right bank (north of the Ishim River), stands as the capital’s only authentic monument of historical and cultural significance. This is one of the oldest burial grounds in Kazakhstan’s capital.

“It appeared long before the city was founded, standing alone in the open steppe. It was named Karaotkel (‘Black Ford’). This was always the shallowest part of the river, near today’s automobile bridge at the intersection of Barayeva Street and Kabanbai Batyr Avenue,” Dmitriy Glukhikh, a local historian from Astana, told Vlast.

The earliest burials date back to 1609. Among those laid to rest here are Sameke Khan, the son of Tayke Khan; warriors of Bogenbai Batyr, Kabanbai Batyr, and Kenesary Khan; Konurkuldza Kudaymendin, the first sultan of Akmolinsk; merchants Baimukhamet Koshchegulov and Valiy Khalfin; as well as Badigul (Babygul-Dzhamaley), the sister of Chokan Valikhanov.

“At least ten thousand people are buried in this cemetery, and 2,169 tombstones have been preserved,” said the historian.

According to him, an outbreak of typhus and cholera occurred in Akmolinsk in 1920. The victims were buried at this cemetery, which was officially closed in 1962, and earmarked for demolition in 1973.

“The cemetery was spared from demolition primarily because it held the graves of those who died from dangerous contagious diseases,” Glukhikh said. “Also, public outrage over the potential destruction of a Chistian cemetery prompted authorities to avoid further conflict. Today, it stands as a protected monument of the capital.”

Azamat Dukombayev, a specialist from the Akishev Institute of Archaeology, believes that the necropolis serves a sacred and religious role and also holds significant value for research.

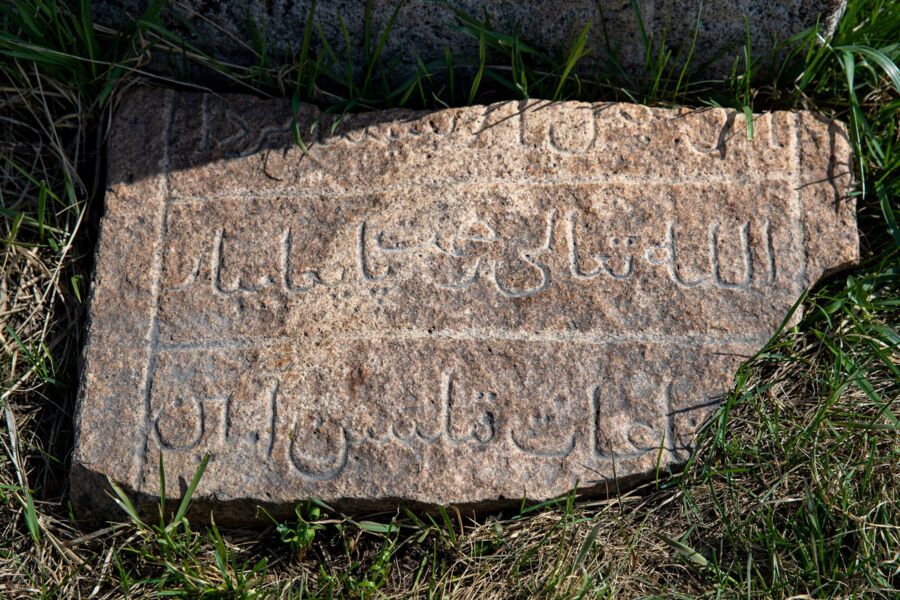

“The Karaotkel cemetery holds historical, architectural, scientific, and memorial value. Field research conducted on its grounds has made it possible to identify not only the boundaries of the necropolis but also the characteristics of its burial practices. Kulpytas [an ancient type of gravestone] are closely linked to the evolution of religious rituals as well as to traditional artistic imagery, styles, and decorative designs,” Dukombayev said.

In his view, studying kulpytas offers new insights into the city’s history and the lives of its people. It also shows how historical events and ideological shifts have shaped religious traditions.

“Epitaphs, inscriptions, tamga, drawings, and symbols — all of these can be studied as separate elements of the cult and memorial traditions of Saryarka. As carriers of historical memory, cemetery monuments preserve the unique features of ethnic culture, as well as important chapters from the life and public activities of the region.” Dukombayev told Vlast.

In addition, the archeologist believes that the memorial and historical complex at the Muslim cemetery holds significant historical and ethnographic value that requires further comprehensive research.

The “Karaotkel” necropolis is a historic Muslim cemetery, but it is not the only one in Astana. According to Glukhikh, there are other cemeteries in the city that few people know about. One is located between Zatayevich Street and the Sarybulak River.

“This other cemetery is mainly the resting place of Chechens and Ingush who died from the typhus outbreak during the deportations. It is located near the railway station, because many either died in the deportation trains or in the hospital near the station. At the time, those who were repressed were not buried in the main Muslim cemetery, and so this cemetery emerged in this area during the 1940s,” Glukhikh said.

It is worth noting that two small cemeteries have also been preserved amid the new urban development of the capital, not far from the former village of Bashan.

“The village was located near Lake Taldykol. The city’s expansion is gradually encroaching on these forgotten graves,” the historian added.

The History of Akmolinsk and Tselinograd Cemeteries

Glukhikh notes that during the Soviet era, Orthodox and Jewish cemeteries in Akmolinsk-Tselinograd were treated with blatant disrespect: They were simply demolished and built over.

If a cemetery had not hosted a burial for 25 years and was not protected by the local administration, it could be demolished according to Soviet legislation.

The first Orthodox cemetery appeared with the founding of the city in 1830. It occupied a large area. From Tserkovnaya Street in the south to Stepnaya Street in the north, and from Krepostnaya Street in the east to Meshchanskaya Street in the west.

“Meshchanskaya Street was originally called Cemetery Street — it was the resting place of the city’s first residents. Alongside simple crosses, there were obelisks, cast-iron and marble headstones, and trees growing across the grounds. The cemetery was closed in 1915, fenced off, and guarded. But in the 1920s, authorities ordered its demolition and the area’s redevelopment. It happened so swiftly around 1922 that there was no time to relocate the graves. For many years afterward, coffins and human remains were still being unearthed during construction in that district,” Glukhikh said.

In the late 1990s, during road repairs on Victory Avenue, a marble tombstone belonging to townsman Gavrila Gribanov was unearthed.

“Such was the sad fate of the remains of the city’s first residents,” Glukhikh said.

The Jewish cemetery, which was also destroyed, dated back to the 19th century. According to Glukhikh, it was built “unofficially” and located outside the city limits, on an island formed by the Ishim River and its old riverbed.

Known as Dacha Island, the area was accessible from today’s Kenesary Avenue, formerly Karl Marx Street. In April 1895, some 200 members of Akmolinsk’s Jewish community petitioned the military governor of Siberia to formally establish a religious congregation and requested the appointment of a rabbi.

“The first official rabbi of Akmolinsk was Shliom Reitbort, who had lived in the Turkestan region since 1876. It was he who consecrated the Jewish cemetery. However, with the rise of Soviet power, burials there were banned, and the cemetery fell into complete neglect. By the early 1960s, a gas equipment factory had been built on the site,” Glukhikh said.

Burials also existed in the very heart of the city, in a small park within the block bordered by Zheltoksan (Komsomolskaya) Street and the central square and also between Begeldinova (Kommunisticheskaya) Street and Abai (Lenin) Street.

“This park originated near the main church of the city, dedicated to Alexander Nevsky, which was blown up in 1940. In 1920, a large mass grave of those who fought for Soviet power was established in the center of this park. In the summer of 1919, on the banks of the Ishim River, 38 people who led the largest uprising against the White Army in this region were executed by the forces of Ataman Dutov,” Glukhikh said.

In 1931, new graves appeared in the park, commemorating the victims of a tragic plane crash. On October 10, 1931, a K-4 aircraft crashed en route from Alma-Ata to Akmolinsk.

These graves were relocated during the park’s reconstruction in 1972. By the time the park became part of the presidential residence, no graves remained,” Glukhikh said.

Building Above the Cemetery

Astana is growing in size and residential houses are often being built near cemeteries or atop former burial grounds. This is an issue that consistently sparks strong emotions among the public. Some believe that living in homes built on or near such sites is unacceptable. Others, however, have no issue purchasing apartments in these areas.

One particular plot in the right bank has drawn significant interest. According to Glukhikh, a cemetery stood at the corner of Saryarka (Delegatskaya) Avenue and Bogenbai Batyr (Pyatiletka) Avenue between 1915-1962.

“The demolition process dragged on until 1979,” Glukhikh said. “Because the public was outraged.”

While many families were able to move the remains of their ancestors, numerous graves remained buried beneath the new roads and apartment buildings, built after the capital was relocated from Almaty to Astana in 1997.

Hieromonk Dimitry (Baydek), the sacristan of the Assumption Cathedral in Astana, refrained from making any definitive statements about whether graves remain beneath urban infrastructure.

“It is possible that something was indeed there, and when they started digging foundations for these buildings, they began to uncover remains and burials. So, it’s quite likely that something occurred there,” Priest Dimitry told Vlast.

The local administration told Vlast that “according to available information, there are no official records indicating the existence of a cemetery at the specified site.”

Priest Dimitry cited Moscow as an example, where many cemeteries in surrounding villages were literally absorbed by the growing metropolis.

“If cemeteries could not be preserved or improved, exhumations and reburials were carried out. But it is very difficult to find relatives and get their consent… It’s easier for the city to simply avoid such sites,” Priest Dimitry.

According to Priest Sergius (Pinigian), there are cemeteries in Astana that are simply not visible.

“Last year, I held a memorial service in the left bank for a war veteran. The local administration allocated a spot in a cemetery near the Deputatsky neighborhood. Everything is neatly fenced off there, you wouldn’t even say it’s a cemetery,” Priest Sergius said.

District Elder Fyodor Burlakov of the New Apostolic Church confirmed historian Glukhikh’s claim. There was indeed a cemetery at that location. According to him, official reburials were carried out only for the remains whose relatives submitted the appropriate requests.

“When construction of those 25-story buildings began, our church was located on the edge of the cemetery. Workers would bring us the remains they found. The workers also reported the findings to the local administration,” Burlakov told Vlast.

The New Apostolic Church building was erected in 1994 near the former cemetery grounds.

“Many people came, entered the church, and asked, ‘Our parents were buried here. Where are they now? Why are there buildings here instead?’ I told them the decision came from the local administration. People asked to pray for the souls of those who were buried here. They still come by,” Burlakov said.

Tombstone Tourism

Visiting historic graves and memorials is often included in tourist routes. The most famous cemeteries even draw guided tours, which provide insight into the history and significance of the sites. This type of travel, known as “tombstone tourism” and getting popular in Western countries, is unlikely to take off in Astana, according to Glukhikh, because the city lacks a monumental cemetery.

“Cemeteries have not been preserved and are not structured. People won’t come here like they do to the Alexander Nevsky Lavra Pantheon [in St. Petersburg], because there are no Suvorov, Lomonosov, Tchaikovsky, or Dostoevsky. In short, there are no world-renowned names. Even the Kensai cemetery in Almaty is not a popular tourist destination,” Glukhikh said.

An edited version of this article was translated into English by Yerassyl Nurlykhanov.

Власть — это независимое медиа в Казахстане.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.

Мы верим, что справедливое общество невозможно построить без независимой журналистики и достоверной информации. Наша редакция работает над тем чтобы правда была доступна для наших читателей на фоне большой волны фейков, манипуляций и пропаганды. Поддержите Власть.

Поддержать Власть